When people ask what did East Berlin smell like the most immediate and powerful answer is coal. The city relied heavily on brown coal, also known as lignite, for heating, and the smell of it shaped the daily environment. In winter, smoke from countless stoves and chimneys drifted through the streets, saturating the air with a thick, earthy, and sometimes acrid odor. It clung to clothing, soaked into stairwells, and even lingered inside apartments long after the fires were out. This smell carried a paradox: it represented both the warmth of survival and the pollution of necessity. For many residents, the smell of coal meant comfort during freezing nights, but it also brought coughing, ash on windowsills, and skies that seemed permanently gray. The coal smoke became so much a part of daily life that it blended into memory, a scent that defined not just the season but the very identity of the city.

Factories and Industry in the Air

Beyond the residential neighborhoods, East Berlin was dotted with factories and workshops, each adding its own aroma to the urban landscape. The metallic tang of iron and steel, the sharp bite of welding smoke, and the heavy exhaust from industrial machinery all floated into the air. These industrial smells served as reminders of East Germany’s emphasis on production and self-reliance, and they told a story about the nation’s priorities during the Cold War. To walk near these industrial zones was to inhale a combination of oil, grease, and dust that became inseparable from the sound of machinery clanking in the distance. For workers, the smell of industry was a badge of labor and perseverance, though for many city dwellers it was simply another unavoidable layer of the sensory atmosphere. When reflecting on what did East Berlin smell like many people recall this industrial perfume as part of the backdrop of everyday life, a smell that hinted at the invisible power structures shaping the city.

Public Transport: Diesel and Dust

The streets themselves contributed heavily to the city’s character, and nowhere was this clearer than in the public transport system. East Berlin’s buses and older trucks mostly ran on diesel, leaving behind a sharp, almost choking exhaust that followed them down crowded streets. Trams screeched along their tracks, sending sparks into the air and stirring up the dusty smell of hot metal. The U-Bahn and S-Bahn stations often carried the damp scent of underground spaces mixed with rust, grease, and occasionally stale air that had nowhere to escape. Daily commuters became accustomed to this blend, associating it with the rhythms of work, school, and social life. For many, what did East Berlin smell like cannot be separated from the image of waiting on a crowded platform, surrounded by the faint stench of fuel and the earthy odor of wet coats drying in the winter air. It was a smell of movement, of the city alive and pulsing, even under the weight of restriction.

Food Markets and the Scent of Bread

Yet, life in East Berlin was not defined only by harsh or industrial smells. Food markets and bakeries often brought relief and contrast, breaking through the heaviness of smoke and exhaust. The smell of fresh rye bread was especially memorable, drifting from early-morning bakeries and reminding passersby of tradition and nourishment. Markets also carried the pungent tang of pickled vegetables, the savory aroma of sausages frying on small stalls, and the earthy freshness of seasonal produce. Supplies could sometimes be limited, but even in scarcity, these smells gave a sense of community and continuity. They brought warmth to daily routines and moments of joy in a society where abundance was rare. To remember what did East Berlin smell like is to recall the comfort of food against the backdrop of grayness, the way the scent of cabbage or baking bread could stand as a quiet act of resilience and hope.

Streets, Courtyards, and Everyday Life

The lived spaces of East Berlin also had their own unmistakable scents. Apartment courtyards carried the mingled odors of laundry hanging to dry in cold air, garbage bins waiting too long for collection, and the dampness of old brick walls that seemed to trap the chill of the climate. In summer, the smell shifted, carrying more earthy and organic notes, especially after rain, when the ground released the scent of wet stone and soil. These courtyards and stairwells often smelled of humanity in its most ordinary form, a mix of cooking, heating, cleaning, and surviving. They offered no perfume of luxury but instead a raw portrait of daily life. For anyone wondering what did East Berlin smell like these intimate domestic odors may be the truest answer, for they reveal the texture of existence more than the grand narratives of politics or history.

Hospitals, Schools, and Institutions

Institutional life in East Berlin also created lasting impressions through smell. Hospitals carried the sharp bite of disinfectant, iodine, and sterile linens, mixed with the faint odor of cooked food from canteens. Schools smelled of chalk dust, waxed floors, and thick vegetable soups cooked in large pots. These institutional aromas became part of the fabric of childhood and public memory, shaping how people remembered formative years. They added another layer to the city’s olfactory identity: the sense of order, routine, and authority wrapped in the sensory world of disinfectant and boiled meals. When people recall what did East Berlin smell like many bring up these institutional smells as deeply tied to childhood, education, and health under a system that prized uniformity.

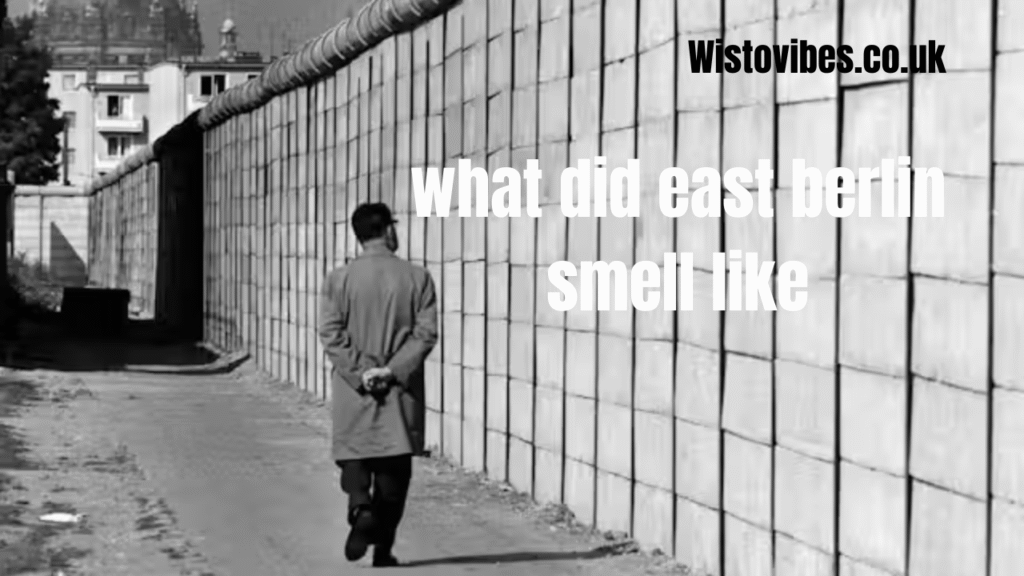

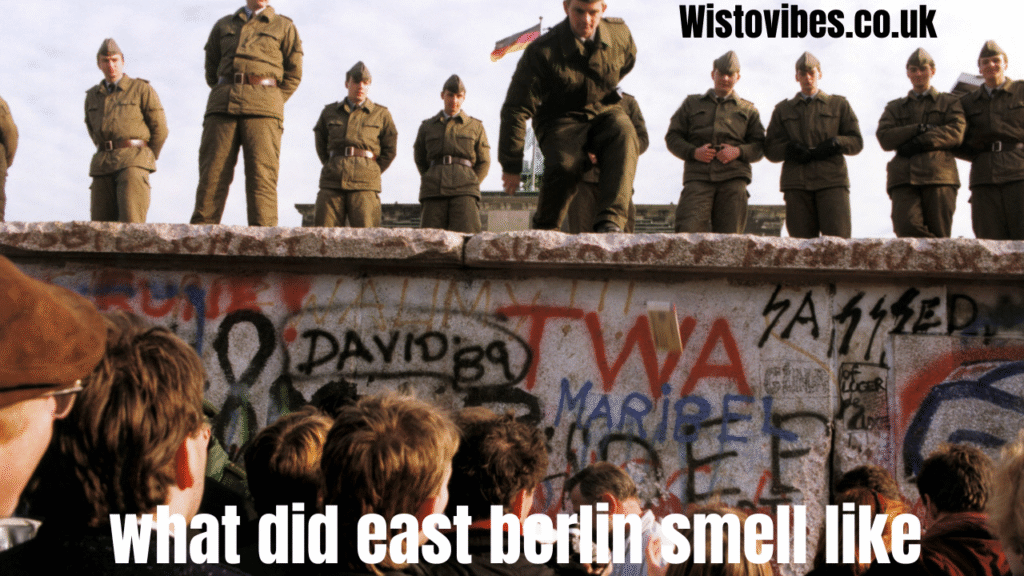

The Wall and Its Checkpoints

The Berlin Wall, both as a physical barrier and a symbol, also carried its own distinctive smell. The concrete in summer gave off a dry, dusty scent, while the checkpoints smelled of asphalt baking under the sun, guard dogs, and the exhaust of military vehicles. For those who crossed or even stood near, the sensory experience was charged with fear and tension, and the smells became part of that memory. They were not only about place but about power and surveillance, reminders that the wall was not simply seen or touched but also smelled. For many, what did East Berlin smell like includes this memory of dust, fuel, and anxiety, scents forever bound to the experience of division.

Contrast With West Berlin

Part of understanding East Berlin’s smell lies in comparison. Visitors who crossed into West Berlin often noticed fresher scents, stronger perfumes, and more abundant food smells. The contrast was striking: while East Berlin bore the weight of coal smoke and scarcity, West Berlin seemed brighter, filled with commercial and consumer smells. This contrast sharpened the memory of East Berlin’s identity, as its olfactory world was inseparable from its political and social position. For those who lived on one side and visited the other, the difference became a defining part of their sensory memory of division. To ask what did East Berlin smell like is also to recognize how its smells were defined by what they were not, by the absence of abundance that existed just across the wall.

Memory, Identity, and Lingering Scents

Even decades after the fall of the Wall, the smells of East Berlin remain vivid in the minds of those who lived there. Smell is a powerful key to memory, stronger in many ways than sight or sound, and for former residents, the scent of coal smoke or cabbage can instantly bring back childhood, family, and moments of survival. For some, these smells bring nostalgia, a longing for lost routines and a sense of community that disappeared with reunification. For others, they are reminders of hardship, pollution, and scarcity. Either way, they continue to shape identity and history, showing that the answer to what did East Berlin smell like is not only factual but also emotional. The smells are remembered as much with the heart as with the nose.

Conclusion: The Invisible History of Scent

So, what did East Berlin smell like It smelled of coal smoke rising from chimneys, of factories and industry working through long days, of diesel and metal from public transport, of bread and cabbage from markets, of disinfectant from institutions, and of dust and asphalt from the Wall itself. It was a city of contrasts, where comforting scents mixed with harsh realities, where the smell of survival existed alongside the scent of restriction. These smells were invisible witnesses to life behind the Iron Curtain, telling stories that words and photographs often cannot. They shaped memory and identity, giving us a way to feel history not just as an idea but as a sensory truth. The scents of East Berlin remind us that history is not only about what we see and hear but also about what lingers in the air, what stays in the nose long after the walls have fallen.

Read More: How to Say She Lives in Berlin in German A Complete Guide